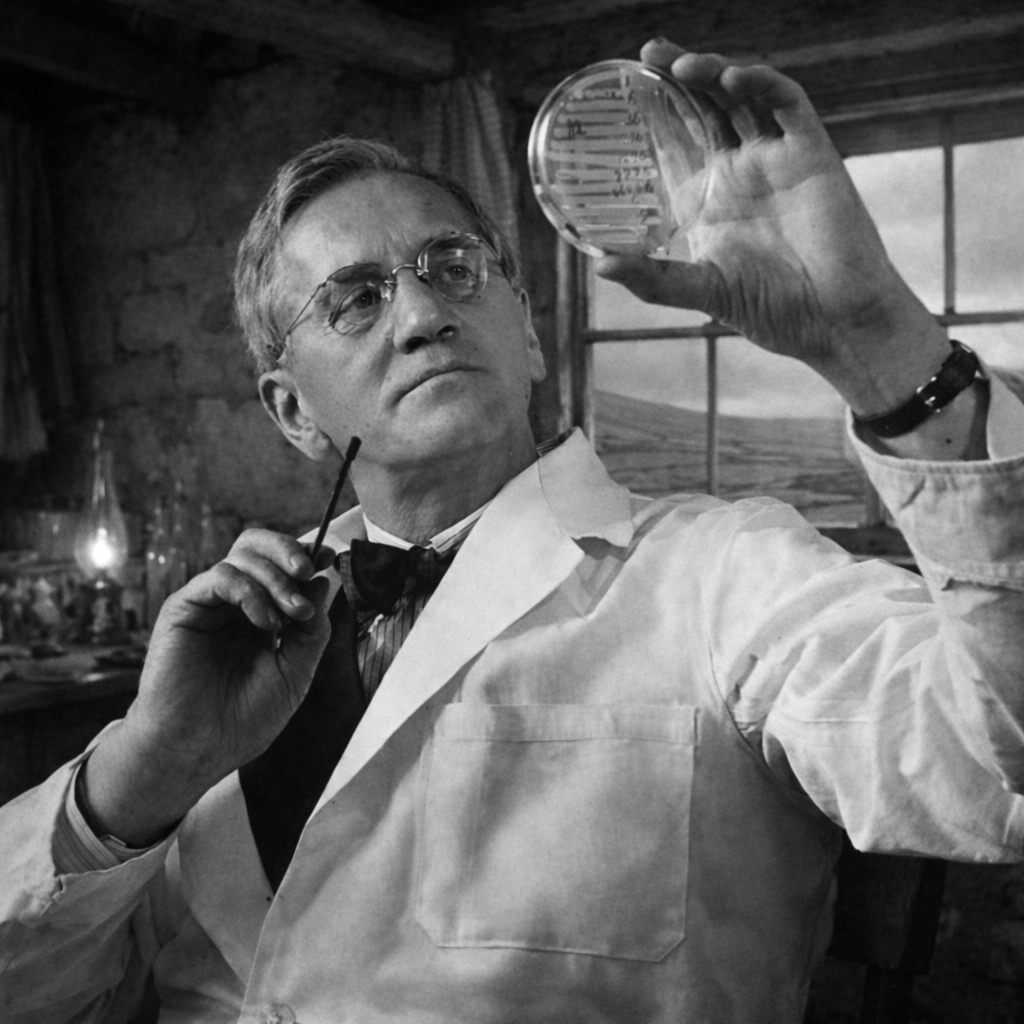

In Part Two of The Unwalked Path we are introduced to Fleming’s journal in which he makes a devil’s brew. This is the link to Part One. The Unwalked Path is fiction. A ‘what might have happened’ story.

Alexander Fleming, Saturday, 9 June 1923, Lochfield Farm. Journal entry #1.

It has been quite an eventful day. In truth, it is the first day of any real interest since our arrival at Lochfield, and I find that this suits me rather well. The purpose of coming here was, after all, to secure a measure of peace and quiet.

After considerable wrangling with Almroth, he at last agreed to my spending the summer here. My brother Hugh, as the eldest, inherited the farm and has kindly placed the cottage at our disposal, along with sufficient space to establish a modest laboratory. It is my intention to pursue some independent work.

In London my research has stalled. I find myself trapped in a repetitive cycle of procedures, productive perhaps, but uninspiring. I am eager to return to the fundamentals—to the excitement of observation, experiment, and improvisation. The war impressed upon me, with brutal clarity, that time is not a luxury we possess. Better methods for the treatment of wounds must be found.

Almroth remains a firm advocate of the carefully constructed experiment, designed to test a clearly articulated hypothesis. In principle, I agree with him. Yet my own experience suggests that an element of chance, properly observed, may yield results of unexpected significance. Most such occurrences prove to be mere curiosities; a few, when interpreted by a suitably sceptical mind, may open entirely new avenues of enquiry and, on occasion, lead to discoveries of considerable consequence.

I have long felt that luck plays a significant role in scientific progress. The previous year offers a useful example. While preparing cultures on a cold winter’s day, a drop of my own nasal mucus inadvertently contaminated an agar plate. Several days later, I observed that the growth of bacteria upon it had been either destroyed or markedly weakened.

Over the following months, I undertook a systematic examination of various bodily fluids—much to the amusement, and occasional protest, of my colleagues—which led to the identification of lysozyme, a naturally occurring enzyme capable of breaking down bacterial cell walls. Its effects are most pronounced against organisms with exposed cell walls (Gram-positive), and considerably less so against those protected by an outer membrane (Gram-negative).

In part, my decision to spend the summer at Lochfield reflects a desire to recover the pleasure of experimentation: to pursue unfamiliar approaches and to test new substances without constraint. I hope that the fresh air and solitude will invigorate my work and quiet those thoughts the war left behind.

Scientific freedom, however, is not my only motivation. After several weeks of gentle persuasion, Sarah has at last agreed to accompany me, rather than remain in London, and I have taken great pleasure in showing her the places of my childhood. Out on the windswept moors of Ayrshire, bleak though they are, I find that we are closer than we have ever been.

So why am I so excited today? It began several days ago, while I was absorbed in my new line of work. As I had promised myself, I resisted the urge to be overly prescriptive, preferring instead a more exploratory approach—casting out a variety of substances to see if any produced an effect of interest. A little bacterial angling, if one permits the analogy.

I selected ten substances with putative antibacterial properties and prepared eight cultures against which to test them, all variants of Staphylococcus. For the most part I relied upon local fungi and plants, though I also included cattle saliva and tears, for the sake of completeness. The collection of materials proved both demanding and, at times, unexpectedly amusing.

Naturally, an increase in tests necessitates an increase in cultures. While the standard strains I brought from London were adequate, I took the liberty of preparing my own. The procedure is straightforward enough:

- Boil a portion of beef muscle—on this occasion kindly supplied by a neighbouring farmer.

- Add partially digested protein in the form of peptones. (I would strongly advise against enquiring further into the particulars of this step.)

- Introduce salt to an approximate concentration of one per cent, to approximate human physiological conditions.

- Inoculate the broth with bacteria obtained from an existing wound. Out of consideration for those of a sensitive disposition (Sarah!), I shall spare the details.

- Allow the mixture to develop until it becomes pleasingly turbid, then store at room temperature.

The result was a rich bacterial stew, synthesised from the Vale’s finest beasts. It may sound appetising; I assure you it is anything but. The stench is rank beyond belief. A strong constitution is required—or, failing that, a handkerchief lightly dusted with Sarah’s bath salts.

Our cleaner, Mrs Kyle, insists upon firmly closing every door between my laboratory and the main house whenever I am engaged in fermenting what she cheerfully refers to as “that Devil’s brew.”

She is not to be messed with. A God fearing, hard-working, straight-talking woman, typical of these part. She demands clear instructions: what is to be done, to what standard, in what order, and to what extent.

I provided her with a written list for the laboratory, and she follows it precisely. I like to think of myself as possessing a disciplined and orderly mind; in truth, I am a messy and often disorganised worker.

For the record, her given name is Margaret, though no one ever calls her anything but Mrs Kyle. She is a gem, and very much to be treasured.

@ Copyright 2026 Steve Gillies. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment