More than halfway now. Fleming walks his way to a clear mind and formulates a plan. This is the fourth part of The Unwalked Path, a fictional tale focused on Sir Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin. Part 3 can be found here. It’s a ‘what might have happened’ tale.

Alexander Fleming, Saturday, 9 June 1923, Lochfield Farm. Journal entry #3.

The road to town followed a winding course, dipping through shallow vales and rising over steep ground—challenging for a horse and trap, perhaps, but easily managed on foot.

More than thirty years ago, my brother and I crossed these same fields daily on our way to school, negotiating makeshift bridges, fences, and hills without a second thought.

Today is fine, the air fresh, and my thoughts occupied as I set out. The walk was some three miles, and I had no intention of hurrying. I meant to take my time and have lunch at the Sheep’s Heid.

I have learned that ideas seldom yield to force. It is often better to allow the mind to wander, to occupy itself elsewhere while the problem quietly works itself out.

The surrounding countryside has always had a calming effect upon me. Even as a child, I was drawn to the high moor, and to the steady, unhurried rhythm of cattle and sheep grazing in the meadows below.

The start of the route was demanding. I do not recall aches or pains from my youth, but now it is a struggle, the path dropping steeply down to the Glen Water before climbing sharply on the far side.

Along the riverbank, the earth is pocked with the small, round entrances of sand martin burrows. They dart in and out, their quick, graceful movements lending busyness to the quiet scene. Happy memories of childhood came unbidden. Too young to handle a rifle, my brothers had taught me various ways to catch rabbits. All involved thrusting an arm into a burrow in the hope of grasping a hind leg, or catching them unawares as they dozed in the sun.

We would approach slowly, careful to avoid eye contact. When close enough—sack or jacket at the ready—we would pounce. You only got one chance.

It was energetic, chaotic fun—though not, I imagine, for the rabbit. I did always feel a pang of sadness at the kill, but it seemed less barbaric than ferreting or the use of snares.

In spring, red grouse and partridge were common, with black grouse appearing less frequently. Peewits, skylarks, and curlews would fill the air with sound. Lone buzzards would patrol the sunny skies until driven down by packs of crows, intent on asserting their dominance. I have often wondered what history lies between such species to justify such persistent hostility.

Looking east, I caught sight of Loudoun Hill—a defiant, silent sentinel of Scotland’s past. I know it chiefly as the site of Robert the Bruce’s early and decisive victory in the struggle for independence; beyond that, my grasp of history is embarrassingly thin. Such is the consequence of attending closely to the small while allowing the larger matters to pass unexamined. One day, when I am done with microbiology, I shall return to these questions and take the time to know properly the land that shaped me.

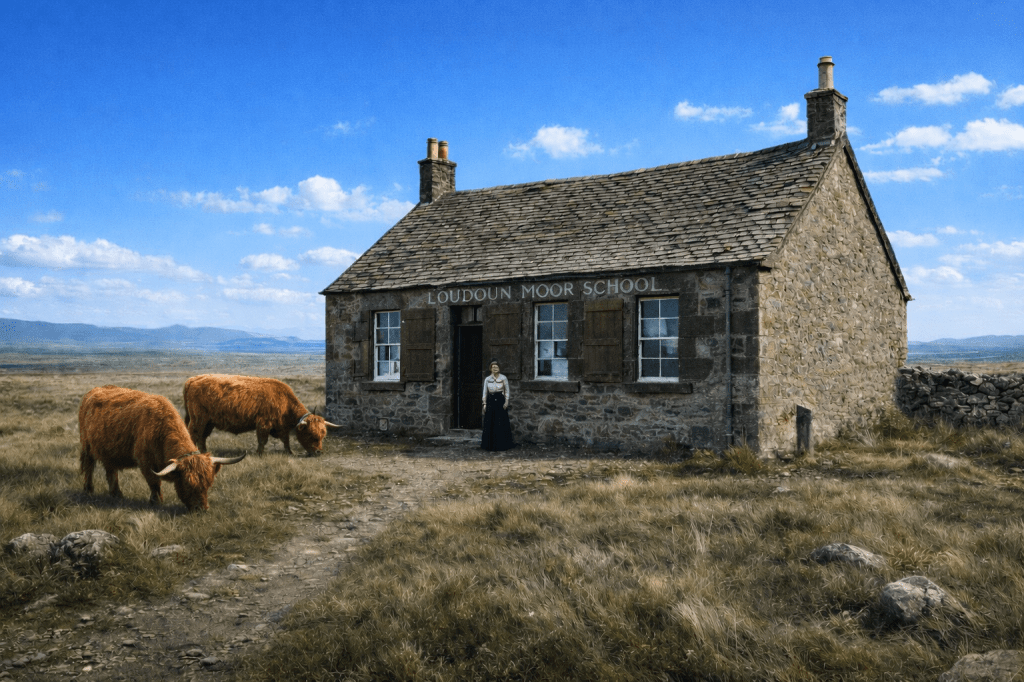

I made my way down the steep slope toward the Glen Water at a measured pace, mindful of the sharper ascent awaiting me on the far side. The Glen is little more than a burn, though it widens here and there enough to permit the occasional cast of a fly. Loudoun Moor School stands at the crest of the hill, oddly silent and deserted in the stillness of a Saturday morning.

Through the large front window I could see, in my mind’s eye, Miss Haddow smiling as she guided the class through their lessons. Bob and I sat at the back of the small room, while the younger children—some no more than five years old—occupied the front rows. I noticed Nell McDonald. She contracted diphtheria in my final year, and I regret to say that I do not know whether she survived. In retrospect, the odds were against her. She was a chatty, friendly girl whom I always liked. It would be good to know what became of her.

On fine days we preferred to work perched on the wide windowsills, soaking up the warmth of the sun. At lunchtime we would wander down to the Glen and sit on the grass. Occasionally Miss Haddow would join us, and on particularly pleasant afternoons she seemed to lose all sense of time.

I remember the walk to school—gruelling in the biting winds of winter, yet a pleasure during the long, golden days of summer. We carried our lunches with us, most often cold porridge and oatcakes wrapped simply. From time to time there would be bread farls, and on rare, special occasions, pottit heid: a meaty preparation of cow’s head, tongue, and brains. Kebbock, a local cottage cheese, was a prized accompaniment to our oatcakes, its creamy sharpness a familiar comfort.

Our mother was well known for her cheese and butter, which she sold through local cadgers—men who travelled from farm to farm by pony and trap, dealing in light goods.

Miss Haddow was likely no more than in her twenties, though to us she appeared far older—possessed of a wisdom well beyond her years. On Monday mornings she would stand at the front of the room and recite a poem or verse by Burns, encouraging us to think on kindness, on nature, and on the wider world beyond our small community. Often her selections carried a quiet lesson; at other times, I suspect, she simply wished to delight us with the rhythm and beauty of the words.

Fridays brought a different kind of reflection. Just before lunch, lessons would pause and we would attend to Miss Haddow’s weekly devotional. She began by reading a short passage from scripture, her voice calm and even, before offering an anecdote drawn from ordinary life to illuminate its meaning. These stories—simple, yet quietly profound—often lingered with me long after the bell had sounded.

As I stood at the window, I found that I could not summon a particular example, yet the essence of those lessons remained clear. They spoke of finding peace amid uncertainty and difficulty, and of a steady presence that endured regardless of circumstance. We were taught that no trial was faced entirely alone.

Those lessons, the natural world that surrounded me, and the sense of community found in small, quiet places have remained with me throughout my life. I am a scientist. I observe, test, experiment, and discover—that is my vocation. My tools are modern: microscopes, vessels, heat, vacuum, and an array of chemical agents. Yet I have never experienced a conflict between science and faith, nor between inquiry and belief. When I study the intricacy and beauty of the world, I see order and pattern of a kind that invites wonder rather than contradiction.

My beliefs were shaped in these hills around Loudoun Moor, where childhood curiosity and enduring truths grew together. Among the heather-covered slopes and familiar glens, the roots of both my questioning mind and my faith took hold, side by side.

Even now, I remain convinced that my education in that small rural school was of the finest kind. Times were hard, and society was only beginning to learn how best to care for children, the vulnerable, and the poor. Yet the school was diligently inspected, attendance carefully recorded, and both doctor and dentist made regular visits from Darvel.

Dentist visits were feared. Toothache was endured until septic boils forced attention. Disease, infection, and illness were common, and attendance records reflected it. Absences were particularly frequent during lambing and harvest. Yet despite these hardships, the education was of the highest quality, and upon my move to London I was quickly advanced beyond my years.

With that, I left Loudoun Moor School behind and turned toward town. The road crested a rise and sloped down toward Darvel. From that vantage I could see the Isle of Arran, its rugged outline etched against the sky. Beyond it, Ailsa Craig stood solitary in the sea, a forgotten monument. The Irish Sea stretched westward, dissolving into the vast reach of the Atlantic beyond.

For a moment I stood still, breathing in the view—the meeting of land and water, immense and yet deeply intimate.

As I began the descent down the steep Burn Road, a plan started to form. I did not dare give it voice—not yet. It remained fragile, ephemeral, like a wisp of smoke or a bubble shimmering in gentle air: close enough to sense, but liable to vanish if grasped too soon. It would come in time. Of that, I was certain.

@ Copyright 2026 Steve Gillies. All right rerserved.

Leave a comment